The Battle of Mactan in a Nutshell

What most people don’t know about the clash between Lapulapu and Magellan

Today is the 500th anniversary of the Battle of Mactan, considered as the first “Filipino” victory against the Europeans, even though the word “Filipino” still didn’t exist in their time, and the concept of “Philippine Islands” wasn’t yet a thing. Almost every Filipino knows the names “Magellan” and “Lapulapu”, and we even named a red fish after the latter. I can still remember the humorous nursery rhyme that we sang during our elementary days: “One plus one, Magellan. Two plus two, Lapulapu.” You know that you made an enormous impact in history when even children sing about you. But here’s the thing, do we really know what actually happened during the battle? Filipinos only learn about Philippine history during elementary, so how we would expect to remember them, let alone to get the facts straight?

“So what really happened and how did it occur?” you might ask. And does the battle made a long lasting impact on our history? We’ll see.

But wait a minute, let’s recap first way back to late 15th century Spain

The spice and gold competition between Spain and Portugal was going more and more intense. Portuguese explorers Bartolomeu Dias discovered another route to the East through the Cape of Good Hope, while later on, Vasco da Gama made his way to Calicut, India, making Portugal have a major stronghold in the world domination. Spain was desperate. Even though the monarchs Fernando and Isabela already made some fortune from Columbus’ “discovery” of the Americas, they are not contented. In order to ease the feud between the two Iberian kingdoms, Pope Alexander VI issued a papal bull in 1493, drawing the so-called Line of Demarcation, splitting the whole globe on where territories they can only explore. Spain was allowed to explore the Americas in the West while Portugal was allowed to control Asia in the East. A year later, this agreement was solidified through their signing of the Treaty of Tordesillas.

But Spain really wanted to go to Asia, as they are so rich with various spices, a luxurious commodity to own in medieval Europe. Spices like cloves, nutmeg, and mace, were extremely expensive that nobles and aristocrats were the only ones who can afford them. Which means, a lot of spices equals to ba-bling ba-bling. Therefore, Spain and Portugal must race against each other on who can find first the islands of Moluccas, aka the Spice Islands, now part of modern-day Indonesia. But since only Portugal can use the eastward route, Spain must devise another way to go to the East, and their solution was to go westward, way beyond the American continents. Even though Portugal already established control in Spice Islands islands, the Spanish crown still desired to claim them.

Enter Ferdinand Magellan (or Fernão de Magalhães in Portuguese, and Fernando de Magallanes in Spanish), a Portuguese explorer and sailor working for King Manuel I. It was not his first time to go to the East Indies, since he was sailing to what is now India, Malaysia, and Indonesia for Portugal since 1505. He told the Portuguese king about his new plan to take the route to the East by going westward. But he was dismissed and deemed ridiculous. It is because sailors used to think that circumnavigating the globe is not only preposterous, but also dangerous due to their fear of sea monsters and killer fogs awaiting for those who dare. Aside from that, he was also being accused of illegal trading, which caused distrust (1). Because of his desire to travel to the East through a new west route, it drove him to negotiate with their rival kingdom, Spain, and abandoned his Portuguese citizenship.

The Beginning of the Expedition

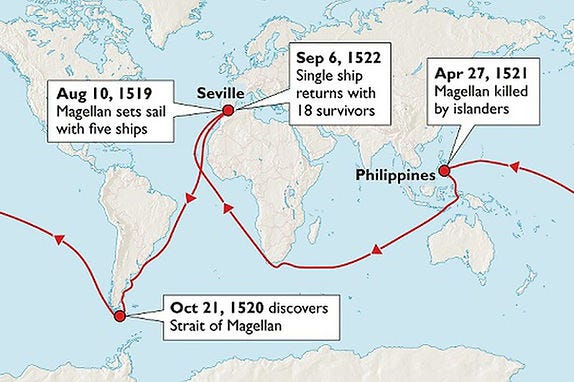

Magellan approached King Carlos I of Spain, aka Emperor Charles V of the Holy Roman Empire, aka That-King-With-A-Horrible-Jaw-Due-to-Habsburg-Inbreeding. He told the Spanish king that he can reach the Spice Islands by west through Atlantic Ocean, going down across South America, until they reach its tip. Due to Spain’s desire to colonize in Asia, the king funded Magellan and gave him 265 troops and 5 galleon ships, namely San Antonio, Concepcion, Trinidad, Victoria, and Santiago. They leaved Spain from San Lucar de Barrameda on September 20, 1519, representing the Spanish flag despite being Portuguese himself.

Magellan and his fleet called the Armada de Molucca sailed across Atlantic Ocean and reached a very narrow passage at the tip of South America near Tierra del Fuego, which was later named Strait of Magellan. They were the first Europeans to sail across the Pacific Ocean, and they were also the ones who named it Oceano Pacifico which means “calm waters”. Magellan was a great captain of the sea, but he was hated by most of his crew, which led to mutinies. Who could blame those Spanish crew if they distrust a rival Portuguese giving them orders? Most of Magellan’s men died from scurvy and starvation due to their unexpectedly long journey to the Pacific. When they arrived at Mariana Islands, dozens of the Chamorro people plundered some of their stuff from their ship Trinidad, which was why Magellan called the islands as Islas de los Ladrones (Island of the Thieves). The next day, they looted and burned Chamorro houses as revenge. And finally on March 16, 1621, they reached the uninhabited island of Homonhon, Samar and stayed there for two weeks (2).

Then in March 28, they arrived at the island of Limasawa in Leyte and encountered the natives. To their surprise, Magellan’s slave called Enrique de Malacca can understand the Malay language of the natives, which lead to their belief that he must have been originated there, an indication that Enrique may have been completed the circumnavigation himself (3). They exchanged goods with the Limasawans, built an alliances with Rajah Kolambu and Rajah Siagu through blood compact, and conducted the first ever Catholic mass in the islands on March 31, where the first Christianization in the Philippines began. Magellan’s men also planted a huge cross there and named the entire islands as Las Islas de San Lazaro, declaring them as a colony of Spain.

With a guide from Rajah Kolambu’s men, Magellan reached Cebu on April 6, and made an alliance with Rajah Humabon through sanduguan. They converted almost 2,200 Cebuanos to Christianity, including the rajah which adopted the name Don Carlos, after the king of Spain. They also gave a baby Jesus image to Humabon’s wife, Juana, and later became known as the Santo Niño de Cebu.

So what happened next? You already know it. Or is it?

What Most Filipinos Think What Happened at the Battle of Mactan

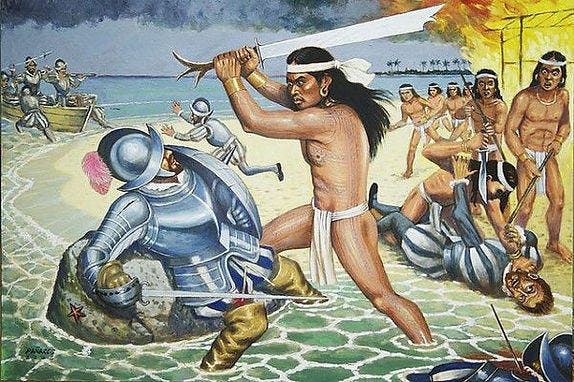

If you’ve ever watched a movie or read a nationalistic textbook detailing how the battle went down, popular culture entailed to most of our minds that Magellan went to the island of Mactan to convert them to Christianity and make them bow to the Spanish crown. But because of the chieftain of Mactan, Lapulapu’s fierce resistance to colonial rule, they fought back with bravery and courage. Lapulapu (or Cilapulapu, according to Pigafetta) is often being portrayed in the media as a fairly young and muscular man with robust physique, as indicated in his portraits and statues. Even though Magellan and his troops were militarily advanced because of their weapons, Lapulapu’s men still fought with honor. We often visualize the battle scene where the chief of Mactan and Magellan were having a one-on-one duel with each other, until the latter was killed. And just like that, Lapulapu became the first “Filipino” to fought against European tyranny, making him our first national “hero”.

But upon critical examination of facts, our interpretation of the event is at best, sensationalized, and at worst, distorted. First of all, historians widely believe that Lapulapu was around 70 years old when the battle occurred (4), making him physically unfit to fight Magellan himself through a one-on-one duel. So no, Lapulapu did not kill Magellan by himself, but by his warriors instead. And second of all, the reasons for their bloody confrontation are more nuanced and complicated that most people think. It is because simplistic and nationalistic retelling of our history is more desirable and palatable to uncritical minds who crave for historical identity. So what is the real story that the documents actually say?

What Actually Happened in History

The only surviving account of the Battle of Mactan from an eyewitness came from Magellan’s Italian historian and chronicler Antonio Pigafetta, who had a tendency to exaggerate his claims, but nevertheless still the most reliable primary source for the event. What we only have is a story from a Eurocentric point of view, and the other side of the story from Lapulapu and Rajah Humabon simply doesn’t exist (at least for now, who knows, maybe future historians will discover something). Almost every thing that we know about Magellan’s expedition came from Pigafetta’s accounts. Therefore, it must be kept in mind that some details might be biased. But it is also important to remember that we cannot fully trust the local legendary accounts either about the life of Lapulapu before and after the battle since they were written centuries after the fact, and assessing their historicity is simply not tenable. So, we must have some kind of a balanced perspective here.

The Rajahnate of Cebu was an affluent kingdom since it was an intersection point between the trade routes of Chinese goods from the Kingdom of Tondo and Muslim pottery from the Rajahnate of Butuan, which made Rajah Humabon rich from the influx of wealth from these trade, and a very powerful leader, superior to other datus. Because of Magellan and Humabon’s friendship, as signified by their blood compact (sanduguan), the rajah ordered to the nearby datus to provide food supplies to the Europeans, and also to convert to Christianity. This gave an impression to Magellan that the Rajah of Cebu is the ultimate local sovereign over other chiefs, and everyone must subdue to him. Every datus near Cebu complied with Humabon’s decree, except one: Lapulapu, the chief of Mactan.

Humabon and Lapulapu were rivals when it come to power. Even though the former created wealth from trade, the chief of Mactan was a threat to him, as he was notorious for being a fearsome pirate that plunders the merchants’ ships before they can even make it to mainland Cebu. It is because Lapulapu has a greater geographical edge, where Mactan is located in a strategic place that allowed him to control the surrounding waters of the island (5). This gave a growing tension and fight for the control of Mactan waters. between the two even before the arrival of the Europeans. Magellan was ignorant on how the chiefdom politics work in the archipelago, as he became used to the system of centralized government system in Europe. Visayan chiefdoms were built on networks of alliances through loose ties and personal allegiance to a much more superior datu or rajah to them. But both Humabon and Lapulapu asserted dominance and superiority, hence the feud. Humabon saw his conversion to Christianity an opportunity to build ties with foreign powers, which can be a way to subdue Lapulapu.

According to Pigafetta (6), the other rival datu of Mactan, Datu Zula, promised Magellan livestock from their island and Christian conversion, but they cannot fulfill their promise because Lapulapu resisted to give in. Humabon and Zula persuaded the Portuguese captain to go to Mactan and confront the datu.

“Friday, the 26th of April, Zula, who was one of the principal men or chiefs of the island of Matan [Mactan], sent to the captain a son of his with two goats to make a present of them, and to say that if he did not do all that he had promised, the cause of that was another chief named Cilapulapu [Lapulapu], who would not in any way obey the King of Spain, and had prevented him from doing so: but that if the captain would send him the following night one boat full of men to give him assistance, he would fight and subdue his rival. On the receipt of this message, the captain decided to go himself with three boats. We entreated him much not to go to this enterprise in person, but he as a good shepherd would not abandon his flock.”

— Antonio Pigafetta (The First Voyage Round the World by Magellan)

Magellan interpreted that Lapulapu was just a misbehaving subordinate datu, that needs to be force to comply with the orders of his superior rajah, without knowing about their existing rivalry. Most nationalistic historians say that Lapulapu’s resistance to Magellan was driven by his anti-colonialist desire to be under the European influence. But according to Cebuano historian and National Artist for Literature Resil Mojares, Lapulapu was actually willing to recognize the power of the King of Spain, but not the authority of Rajah Humabon (7). In other words, the Battle of Mactan was not really a heroic defense of indios against the tyrannical conquistadores, but more like a episode of two warring rival sandwich states, where Magellan and his crew became the sandwich dressing between them. Despite of that, his aspirations to Christianize the whole Visayan islands and make them a Spanish colony was still standing in his mind.

When Magellan arrived at Mactan the night before the battle, he was backed by Rajah Humabon, Datu Zula, and their newly converted natives, but they were told to just watch from afar, and let the Spaniards do the talking. The captain gave an ultimatum to Lapulapu: recognize the authority of the Christian Rajah of Cebu and the Kingdom of Spain, or prepare for violence. The Mactan chief was decided to choose the latter, but he requested to postpone the attack until the morning. The conquistadors were baffled at first, but it turned out to be a delaying tactic by Lapulapu to gather more men.

“We set out from Zubu [Cebu] at midnight, we were sixty men armed with corslets and helmets; there were with us the Christian king [Humabon], the prince, and some of the chief men, and many others divided among twenty or thirty balangai. We arrived at Matan [Mactan] three hours before daylight. The captain before attacking wished to attempt gentle means, and sent on shore the Moorish merchant to tell those islanders who were of the party of Cilapulapu, that if they would recognise the Christian king as their sovereign, and obey the King of Spain, and pay us the tribute which had been asked, the captain would become their friend, otherwise we should prove how our lances wounded. The islanders were not terrified, they replied that if we had lances, so also had they, although only of reeds, and wood hardened with fire. They asked however that we should not attack them by night, but wait for daylight, because they were expecting reinforcements, and would be in greater number. This they said with cunning, to excite us to attack them by night, supposing that we were ready; but they wished this because they had dug ditches between their houses and the beach, and they hoped that we should fall into them.”

— Antonio Pigafetta (The First Voyage Round the World by Magellan)

It was already morning of April 27, 1521, and Magellan prepared his 49 troops to fight, prepared with guns, swords, crossbows, shields, and metal armors. Even though the Spaniards have a more advanced weaponry, Lapulapu and his men still have the greater advantage. The shores of Mactan were full of rocks and coral reefs, which prevented Magellan’s ships to land near the beach. As a result, firing guns, cannons, and crossbows from the ships had little to no effect on inflicting damage to the natives as they can just easily avoid the fired muskets and crossbow arrows due to extreme distance from the shore, making them essentially useless. And for the same reason, Magellan cannot command them to stop, until they run out of ammunition. Aside from that, Magellan’s men were severely outnumbered. Pigafetta, which was one of the 49 soldiers who fought in Mactan, estimated that Lapulapu’s men were 1,500 in total (8).

Immediately after they landed on the shore, Mactan natives bombarded them with poisoned arrows, iron-tipped spears, fire-hardened sticks, and stones. Damage on them were not that severe, as they were protected by their iron armors and helmets. But Lapulapu’s men were brilliant, they started to aim at their unarmored legs. With hopes to deescalate the whole situation, Magellan ordered some of his men to burn down some 20 to 30 houses in order to instill fear on the natives and to show a sign that they were messing with the wrong guys. But jokes on him, Lapulapu’s men just became more pissed off, giving them more reasons to fight back. Until Magellan was finally shot with a poisoned arrow on his right leg. It became the Mactan natives’ opportunity to specifically attack the captain. He was wounded on his arm with a bamboo spear, and suffered a heavy blow on his left leg with a “scimitar” (which was likely a kampilan), which caused him to fall onto his face downward on the waters. Afterwards, Lapulapu’s men ambushed the wounded Magellan with spears and swords repeatedly, killing him in the process. Pigafetta witnessed how his captain was murdered by the natives, and found enough time to escape.

“Thus we fought for more than an hour, until an Indian succeeded in thrusting a cane lance into the captain’s face. He then, being irritated, pierced the Indian’s breast with his lance, and left it in his body, and trying to draw his sword he was unable to draw it more than half way, on account of a javelin wound which he had received in the right arm. The enemies seeing this all rushed against him, and one of them with a great sword, like a great scimetar gave him a great blow on the left leg, which brought the captain down on his face, then the Indians threw themselves upon him, and ran him through with lances and scimetars, and all the other arms which they had, so that they deprived of life our mirror, light, comfort, and true guide.” — Antonio Pigafetta (The First Voyage Round the World by Magellan)

Pigafetta estimated that eight of their crew were killed, plus one including Magellan, while four from Christian Cebuanos perished, and 15 men from Lapulapu were lost. The historian himself was one of the wounded. Meanwhile, Rajah Humabon and Datu Zula were just from afar, watching the whole mess happen before their eyes and not offering any kind of back-up. The Spaniards left Mactan with a great shame on their faces, while surviving loyalists lamented the death of their captain. Magellan died without even accomplishing his goal of going to Moluccas, and not finishing his circumnavigation trip.

What Happened After the Battle?

Magellan’s survived loyalists begged Rajah Humabon to claim the corpse of their captain and eight other men, and were even willing to pay the victors as much as they wanted, but Lapulapu notedly refused. It seemed that they wanted to keep his remains as their war trophy (9). Meanwhile, another Portuguese explorer and Magellan’s brother-in-law Duarte Barbosa and Juan Serrano were elected as the new captains of Armada de Molucca. But due to their loss at the Battle of Mactan, Cebuanos lost their respect to the Spaniards, while their abusiveness became more obvious. Magellan’s will allegedly included his request to liberate his slave Enrique de Malacca, but the two new captains demanded him to continue his translating duties and follow their orders. According to historian Gregorio Zaide, Barbosa reportedly became abusive to Enrique. So, he developed a conspiracy plot with Rajah Humabon to betray and kill the remaining Europeans, and they executed the plan (10).

It was May 1, 1521 when Humabon conducted a feast with the Spaniards, which attended by 30 men who were mostly officers. After the meal was ended, armed Cebuanos entered the hall and massacred 27 of them, including Barbosa and Serrano. Out of fear, the remaining Spaniards hurriedly escaped Cebu and went towards of what was now known as Indonesia. They finally reached Moluccas at the island of Tidore and greeted by the islands’ leader Sultan Al-Mansur. They exchanged goods such as clothes, knives, and glassware with spices. The two remaining ships, Trinidad and Victoria, parted ways where the former planned to take their route to Mexico, while the latter planned to travel westward to go back to Spain. Unfortunately, Trinidad was plundered and sacked by Portuguese forces in Moluccas, making Victoria the only surviving ship. Juan Sebastian Elcano, the captain of Victoria, led the expedition for their return to Spain by sailing across the Indian Ocean, down to the Cape of Good Hope, and up to the western side of Africa, until they went back to San Lucar de Barrameda on September 6, 1522, making Elcano the official first European to circumnavigate the globe. Only 18 of them out of 265 crew survived.

So about about the other three ships? Why was Victoria the only survivor?

- San Antonio was abandoned while passing on the Strait of Magellan on November 1520, and returned to Spain on May 1521.

- Santiago was shipwrecked during a storm in Santa Cruz River in Argentine on May 1520.

- Concepcion was deliberately burned down in the Philippines on May 1521.

The Battle of Mactan’s Historic Significance

Overall, despite of the less nationalistic reasons of the battle than we thought, Lapulapu’s victory managed to scare the Spaniards away, and delayed the Spanish colonization for 44 years, until Miguel Lopez de Legazpi’s conquest in 1564 to 65. If Magellan and the conquistadors won that bloody conflict, we may have been colonized by Spain for total 377 years, instead of just 333 years.

However, think about it, is Lapulapu really deserved to be called the first “Philippine national hero”? As we’ve established earlier, his motivations to fight Magellan weren’t that nationalistic and anti-colonialist, compare to our other heroes like Dagohoy and Bonifacio. He didn’t defended his island of Mactan against a Western oppressor, but only expelled a combatant from a rival chief. But nevertheless, we created him as our own symbol of nationalism during the times that we need to have a historical identity. Filipinos transformed him as a “native Filipino” hero who successfully fought the conquistadors. After all, isn’t that what our heroes for?

Of course, modern day Spaniards and Filipinos have conflicting portrayals on how Magellan and Lapulapu were viewed in their own histories. Historian Laurence Bergreen said in his book Over the Edge of the World that Magellan was interpreted in the Philippines as “an invader and murderer” instead of “a courageous explorer”, while Lapulapu was “romanticized beyond recognition” that “if not for his battle with Magellan, his name would be lost to history,” considering that there are no other official historical records on Lapulapu’s life, even during his reign (9).

“Within the harbor, a white obelisk commemorates the ferocious battle between the Europeans and the Filipinos, and it offers two sharply varying accounts of the events. One face presents the European point of view: ‘Here on 27th April 1521 the great Portuguese navigator Hernando de Magallanes, in the service of the King of Spain, was slain by native Filipinos.’ The other portrays the conflict from the Filipino perspective: ‘Here on this spot the great chieftain Lapu Lapu repelled an attack by Ferdinand Magellan, killing him and sending his forces away.’ This version is naturally more popular in the Philippines, where the name Magellan is often regarded with loathing and even gloating at the circumstances of his death. Every April, Filipinos restage the battle of Mactan on the beach where it occurred, with the part of Lapu Lapu played by a film star, and Magellan by a professional soldier. Thousands turn out to witness the reenactment between the nearly naked Filipino warrior and the armor-clad invader who eventually falls face down into the surf.”

— Laurence Bergreen (Over the Edge of the World: Magellan’s Terrifying Circumnavigation of the World)

History is truly more complicated than we think, and keeping it simplified is often vulnerable to distortion. There are always multiple sides of the story, and it is foolish to portray historical figures as only good or only evil, even though in this case, we only know about the European side. We gotta read between the lines. A critical reading of historical events will not somehow diminish its value and impact that it caused to our country’s rich history. The battle’s 500th anniversary is still worth celebrating.

Bibliography:

(1) Blakemore, E. (2019). Magellan was first to sail around the world, right? Think again. National Geographic. Retrieved from https://www.nationalgeographic.com/culture/article/magellan-first-sail-around-world-think-again

(2) Agoncillo, T. (2006). Introduction to Filipino History. Garotech Publishing.

(3) Cameron, I. (1974). Magellan and the first circumnavigation of the world. London: Weidenfeld & Nicolson.

(4) Ocampo, A. (2019). The Battle of Mactan, according to Pigafetta. Philippine Daily Inquirer. Retrieved from https://opinion.inquirer.net/122348/the-battle-of-mactan-according-to-pigafetta

(5) Umali, J. (2019). Was Lapu-Lapu Really That Heroic? Esquire Magazine Philippines. Retrieved from https://www.esquiremag.ph/long-reads/features/was-lapu-lapu-really-that-heroic

(6) Pigafetta, A., Stanley, H. E. J. (1874). The First Voyage Round the World by Magellan: Translated from the Accounts of Pigafetta and Other Contemporary Writers. Cambridge University Press, London, United Kingdom.

(7) Limpag, M. (2020). Lapulapu was ready to submit to the King of Spain just not to Humabon: historian. MYCEBU.PH: RE/DISCOVER CEBU. Retrieved from https://mycebu.ph/article/lapulapu-resil-mojares/

(8) Angeles, J. A. (2007). The Battle of Mactan and the Indigenous Discourse on War. Philippine Studies, Vol. 55, №1, pp. 3–52.

(9) Bergreen, L. (2003). Over the Edge of the World: Magellan’s Terrifying Circumnavigation of the World. HarperCollins e-books.

(10) Zaide, G., Zaide, S. (2011). Kasaysayan at Pamahalaan ng Pilipinas: Ikaanim na Edisyon. All Nations Publishing Co. Inc.

Published on April 27, 2021